Using a Kaggle Dataset to Train a ML Model in Google Colab

In a prior post, we learned how to write a React app that uses a Hugging Face ML model to predict data. But what if there’s no ML model that fits your needs? Well, if you have a bunch of data, you can train your own model. Over the next few minutes, we’ll show you how to find a dataset on Kaggle, train a model in Google Colab, and save it for future use.

Let’s say that you want to be able to predict the star rating of a product based on the comment that the user is leaving. If they say “Best product ever!”, they’ll probably give it 5 stars. If they say “This product sucks!”, they’ll probably give it 1 star.

We will want to:

- Find a dataset on Kaggle.

- Create a Google Colab notebook to train our model.

- Get the dataset into Google Colab.

- Wrangle the data to get it ready for training.

- Split the data into training and testing sets.

- Convert the text data into a numerical format.

- Train a model to predict the star rating based on the review.

- Evaluate the model to see how well it works.

- Perform a sanity check to see if the model works.

- Save the trained model so we can use it in an app.

Step 1: Find a Dataset on Kaggle

Kaggle has a ton of datasets and they’re organized well.

- Go to Kaggle Datasets. You can either browse the datasets or use the search box to find a dataset that fits your needs. I’m going to search for “product reviews”. The first result I see is called Amazon Product Reviews.

- Once you’ve found a dataset, download it to your local machine and unzip it.

Tip: There are ways to get the dataset into Colab without downloading it to your local machine, but for this tutorial, we’ll keep it simple and download it locally.

Step 2: Set Up Google Colab

Google Colab is a free cloud-based Jupyter notebook environment.

- Go to Google Colab.

- Create a +New Notebook.

- You might want to rename the notebook to something meaningful. I’m going with “Kaggle Product Reviews”.

- Upload your Kaggle dataset to the notebook by clicking on the folder icon in the left sidebar and hitting the “Upload to session storage” button.

Note: The uploaded file will only be available during the current session. If you close the notebook, you’ll need to re-upload the file.

Step 3: Get the Kaggle dataset into Google Colab

- Import the file.

import pandas as pd

try:

df = pd.read_csv('Reviews.csv')

print(df.head())

except FileNotFoundError:

print("Error: Reviews.csv not found. Make sure the file exists.")

except pd.errors.ParserError:

print("Error: Couldn't parse Reviews.csv. Please check the file format.")

except Exception as e:

print(f"An unexpected error occurred: {e}")- Understand the data.

df.head() # Display the first few rows of the dataset

df.shape # Get the shape of the dataset (rows, columns)

df.info() # Get a summary of the dataset

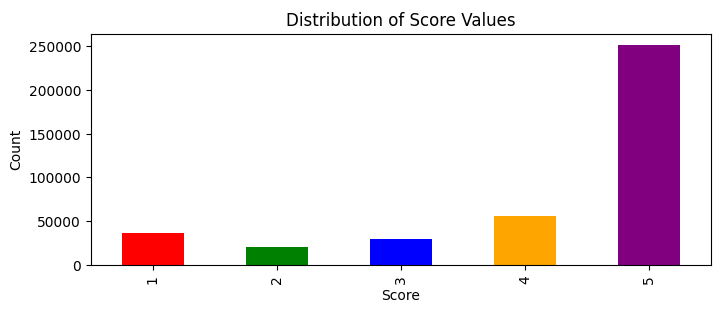

df.describe() # Get a statistical summary of the datasetIn my dataset, I see that the mean (average) rating is 4.2 which means that most reviews are very positive. This is going to result in a model that is biased towards predicting 5 stars. In a later step, we will need to balance the dataset.

This is an example of the kind of thing you might discover when exploring your dataset. YMMV!

Step 4: Clean the data

This step and the next take the most thinking. In this step, we want to wrangle the data into a format that we can use to train our model. The data should be free from:

- irrelevant data. Eliminate columns and parts of columns that we don’t need to train our model

- missing values

- nonsensical values (scores > 5 stars or < 1, whole numbers only, etc.)

- duplicates

Note: Your mission and dataset will vary, so this step will be different for each situation and unfortunately, you need to know your data wrangling skills to get this right.

In this case, we want to predict the star rating based on the review text. So here are my steps:

- Drop any columns that are not relevant to our prediction. We only need the Score, Summary, and Text columns.

df = df[['Score', 'Summary', 'Text']]

# or

df.drop(['Id', 'ProductId', 'UserId', 'ProfileName', 'HelpfulnessNumerator', 'HelpfulnessDenominator', 'Time'], axis=1, inplace=True)- Drop any rows that have missing values.

df.isnull().sum() # Check for missing values

df.dropna(inplace=True) # Drop themThis dataset had only 27 missing Summary values so we dropped them.

- Check for weird values. Score must be a whole number between 1 and 5.

df['Score'].unique() # Check unique values

df = df[(df['Score'] >= 1) & (df['Score'] <= 5)] # Keep only valid scoresThis example dataset had only good Scores. Nothing needed to be dropped but I kept the command in the cell above for your reference.

- Check for duplicates.

df.duplicated().sum() # Check for duplicates

df.drop_duplicates(inplace=True) # Drop duplicatesThis dataset had 173,000 duplicates. So we dropped them, leaving us about 395,000 rows.

- Redistribute the dataset.

Remember from above that the dataset is biased towards 5 stars?

If our intent were to predict an overall star rating keeping in mind the entire dataset, we would want to keep the balance and our predictions would be centered around 4.2 stars. But we want to predict the star rating based on the review text only, ignoring all other ratings. We need to balance the dataset to have an equal number of each star rating, 1 through 5. This is called a “stratified sample”.

The rating with the fewest occurrences is 2 stars. There were 20,845 of them. So I decided to randomly sample 20,845 reviews from each of the Score groups.

stratified_sample = df.groupby('Score').apply(lambda x: x.sample(20_845), include_groups=True).reset_index(drop=True)

stratified_sample['Score'].value_counts()Now each Score group has 20,845 reviews - an even distribution.

Step 5: Clean the text data

The human-entered Summary and Text is messy. Let’s clean them up with nltk, a Python-based natural language toolkit.

Tip: You can also use spaCy for this.

- Convert all text to lowercase so that “Best”, “best” and “BEST” are treated as the same word.

stratified_sample['Summary'] = stratified_sample['Summary'].str.lower()

stratified_sample['Text'] = stratified_sample['Text'].str.lower()Note: At this point I was tempted to remove all the HTML tags from the text. But I decided to leave them in for this example. If you want to remove them, use this code.

- Remove Punctuation

import string

stratified_sample['Summary'] = stratified_sample['Summary'].str.translate(str.maketrans('', '', string.punctuation))

stratified_sample['Text'] = stratified_sample['Text'].str.translate(str.maketrans('', '', string.punctuation))Note: Punctuation adds meaning but we need to keep it simple for this example. If you want to keep it in, use BERT or another transformer that can handle punctuation.

- Tokenize the sentences into individual words

import nltk

from nltk.tokenize import word_tokenize

nltk.download('punkt')

nltk.download('punkt_tab')

stratified_sample['Summary'] = stratified_sample['Summary'].apply(word_tokenize)

stratified_sample['Text'] = stratified_sample['Text'].apply(word_tokenize)This converts the sentences into lists of words. For example, “Best product ever!” becomes [“best”, “product”, “ever”].

- Remove common words

Words like “I”, “you”, “and”, “the”, “is”, “are”, etc. are called stop words. They don’t add much meaning to the text and can be removed. nltk provides us with a list but it includes negation words like “not” and “no”. That’s pretty bad in our case. Just imagine if you stripped “not” from this sentence: “It was not bad at all!”. It completely changes the meaning; it changes the valence. To stay truer to the origninal valence, we’re excluding the negation stop words from nltk’s list. You’ll likely want to do this for any NLP (natural language processing).

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

negation_words = {

'no',

'not',

'none',

'neither',

'never',

'nobody',

'nothing',

'nowhere',

'dont'

}

nltk.download('stopwords')

stop_words = set(stopwords.words('english'))

# Allow negation stop words -- they're important for TF-IDF

filtered_stop_words = stop_words - negation_words

stratified_sample['Summary'] = stratified_sample['Summary'].apply(lambda tokens: [word for word in tokens if word not in filtered_stop_words])

stratified_sample['Text'] = stratified_sample['Text'].apply(lambda tokens: [word for word in tokens if word not in filtered_stop_words])- Reduce words to their root form

Lemmatization is reducing words to their base, like “running”→“run” or “better”→“good”.

from nltk.stem import WordNetLemmatizer

nltk.download('wordnet')

lemmatizer = WordNetLemmatizer()

stratified_sample['Summary'] = stratified_sample['Summary'].apply(lambda tokens: [lemmatizer.lemmatize(word) for word in tokens])

stratified_sample['Text'] = stratified_sample['Text'].apply(lambda tokens: [lemmatizer.lemmatize(word) for word in tokens])Note: You can also use stemming instead of lemmatization. Stemming is faster but less accurate. Stemming removes prefixes and suffixes, like “happiness”→“happi” or “played”→“play”. Use nltk’s PorterStemmer or SnowballStemmer for this.

- Join the tokens back into a single string

We broke them into “words” so each word could be processed. All the words are now clean, so we must join them back together into meaningful sentences for training.

stratified_sample['Summary'] = stratified_sample['Summary'].apply(lambda tokens: ' '.join(tokens))

stratified_sample['Text'] = stratified_sample['Text'].apply(lambda tokens: ' '.join(tokens))We now have sentence again, but sentences that sound like Kevin from The Office. Instead of “I love this extremely good product!”, we have “love extreme good product”.

Step 6: Split the Data into Training and Testing Sets

To evaluate your model, you’ll split the data into training and testing sets:

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# Define features (X) and target (y)

X = stratified_sample[['Summary','Text']]

y = stratified_sample['Score']

# Split the data (80% training, 20% testing)

(X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test) = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42)Step 7: Vectorize the text data

Machine learning algorithms work with numerical data but our Summary and Text are strings. So we need to convert them into a numerical format. There are many algorithms to do this. We’ll use TF-IDF from scikit-learn.

- Vectorize the text data.

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import TfidfVectorizer

vectorizer_summary = TfidfVectorizer(max_features=10_000) # Limit to the most important 10,000 unique words

vectorizer_text = TfidfVectorizer(max_features=10_000)

X_train_summary = vectorizer_summary.fit_transform(X_train['Summary'])

X_test_summary = vectorizer_summary.transform(X_test['Summary'])

X_train_text = vectorizer_text.fit_transform(X_train['Text'])

X_test_text = vectorizer_text.transform(X_test['Text'])

# Combine the two vectors

import scipy.sparse as sp

X_train_combined = sp.hstack([X_train_summary, X_train_text])

X_test_combined = sp.hstack([X_test_summary, X_test_text])Note: I was tempted to fit the entire dataset, then split the training and testing sets and transform them individually. But that would have leaked information from the test set into the training set. When testing is done later, the accuracy score would have been exaggerated. Think about it; when running the model in the future, we have no idea what words will be used. For an accurate test, we must treat the test set as if it were new data.

Look here for a great explanation of fit() vs transform() vs fit_transform().

Step 8: Train a Machine Learning Model

Choose a machine learning algorithm and train your model. Since all of our outcomes are in categories (1 through 5), we’re going to choose a Random Forest classifier.

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

model = RandomForestClassifier(random_state=42)

model.fit(X_train_combined, y_train) # <-- Train the modelNote: If it were a regression problem (predicting a continuous value), you would use a different algorithm, like Linear Regression or Decision Trees.

Step 9: Evaluate the Model

We’ve now got a model that can predict the star rating based on the review text. Let’s see how well it works by evaluating it on the test set.

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

# Make predictions

y_pred = model.predict(X_test_combined)

accuracy = accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred)

print(f"Model Accuracy: {accuracy:.2f}")The accuracy score will be between 0 and 1. A score of 0.8 means that the model correctly predicted the star rating 80% of the time. Ours was a dismal 0.51. 😦 This may have been because a close guess is still seen as 100% wrong (unlike in a regression model). So if we predicted a 2-star review but it was 1 or if we predicted a 4-star review and it was 5, those would still be considered completely wrong. In classification, there’s no such thing as close. Let’s try with some hand-written reviews.

Step 10: Perform a Sanity Check

Perform a quick sanity check by predicting a few single values. We’ll write three reviews, one each for a 1-star, 3-star, and 5-star rating. Let’s how closely the model predicts.

test_5_star_summary = 'Wonderful!'

test_5_star_text = 'This is an amazing product. I love it!'

test_5_star_vectorized_summary = vectorizer_summary.transform([test_5_star_summary])

test_5_star_vectorized_text = vectorizer_text.transform([test_5_star_text])

test_5_star = sp.hstack([test_5_star_vectorized_summary, test_5_star_vectorized_text])

prediction = model.predict(test_5_star)

print(f"Expected 5 star. Actual prediction: {prediction}")

test_1_star_summary = 'Terrible'

test_1_star_text = 'This was a very bad product. I hated it!'

test_1_star_vectorized_summary = vectorizer_summary.transform([test_1_star_summary])

test_1_star_vectorized_text = vectorizer_text.transform([test_1_star_text])

test_1_star = sp.hstack([test_1_star_vectorized_summary, test_1_star_vectorized_text])

prediction = model.predict(test_1_star)

print(f"Expected 1 star. Actual prediction: {prediction}")

test_3_star_summary = 'Just okay'

test_3_star_text = 'It was alright I guess. Barely worked.'

test_3_star_vectorized_summary = vectorizer_summary.transform([test_3_star_summary])

test_3_star_vectorized_text = vectorizer_text.transform([test_3_star_text])

test_3_star = sp.hstack([test_3_star_vectorized_summary, test_3_star_vectorized_text])

prediction = model.predict(test_3_star)

print(f"Expected 3 stars. Actual prediction: {prediction}")These resulted in predictions of 5, 1, and 3 stars respectively. Perfect! Looks like our model works pretty well after all.

Step 11: Save the Model for Future Use

Finally, let’s save our trained model in Python’s pickle format so we can use it later without retraining. This is especially useful if you’re going to deploy the model in a web app or use it in another project.

import pickle

filename = 'star_rating_from_Summary_and_Text.pkl'

with open(filename, 'wb') as f:

pickle.dump(model, f)

print(f"Model saved as {filename}")You can now download the trained_model.pkl file from Colab and use it in other projects.

Conclusion

If you made it this far, nice work! You’ve successfully trained a machine learning model in Google Colab using a Kaggle dataset. This workflow — dataset selection, data wrangling, training, evaluation, and saving — is pretty much the same for any ML training project. Of course, the methods will vary wildly depending on the dataset and the problem you’re trying to solve. But the overall process is the same.

Reach out if you have questions or comments or want some training. I’m always happy to help.